Fifty Years Later: How Alabama Law Alumni Reformed the Alabama Judicial System

By Savannah Kelly

When Alabama became a state, the Common Law of England mandated the way that courts and judicial procedure operated. This included back-and-forth pleadings, many technicalities, and a court system that was difficult for even the most practiced lawyer to understand.

In 1973, Article VI, also known as the Judicial Article, was passed to reform the judicial system in Alabama. Before then, the judicial system was controlled by the legislature, not the courts. As part of his efforts to reform the judicial system, Chief Justice and Senator Howell Heflin (Class of 1948) convinced the state legislature to confer rule-making power on the state Supreme Court rather than the legislature, resulting in the drafting of the Rules of Civil Procedure just two years prior to the passage of the Judicial Article. Many Alabama Law alumni were involved in the effort to reform the judicial system as the “foot soldiers” to Heflin, whose tenacity and passion for judicial reform led to the largest reform in the State since the 1901 Constitution.

Judicial Reform: A Long Time Coming

Prior to the reform in 1973, Alabama had 85 limited jurisdiction trial courts — excluding municipal and probate courts — all of which had different rules and procedures that varied from county to county. This caused confusion for citizens who had to go through the courts because the expectations of the various courts throughout the state lacked any form of consistency or systemic organization. This led to a backlog of cases, some of which took four to five years to make it through the system. At the time, Charles Cole, a professor at Cumberland Law, described Alabama’s court system as “a non-system of courts of varied jurisdictions that were not subject to any centralized administration or accountability.” In addition to being completely decentralized, the legislature – not the judiciary – was tasked with making the rules that dictated how the courts operated. This meant that, oftentimes, judges bent to the will of legislators. The question of the balance of power was “seldom raised,” so the courts were left as-is.

“There was no unified court system in Alabama; it was a collection of all different types of jurisdictions and systems,” said Mike House, former chief of staff to Howell Heflin during his tenure as Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice and later as Senator. “You had Appellate Courts, Circuit Courts, and a conglomeration of a variety of courts at the lower county and municipal level. You even had some cases where the Probate Judge was also the County Judge, and, in many instances, it was used to keep Black people down in the Blackbelt.”

This lack of organization and unification at lower-level courts led to a broken Justice of the Peace system in which many of the departments were corrupt. Citizens were picked up for low-level crimes, taken to a Justice of the Peace facility – often a trailer – and made to pay the fine then and there without a trial. The fines were frequently split between the Justices and their sheriffs. The Justices of the Peace faced no regulation, scrutiny, review, or audits. Essentially, they were free to do as they pleased.

Though there had been some efforts to reform the broken system since the implementation of the 1901 Constitution, Governor Emmet O’Neal is credited with beginning the judicial reform effort in Alabama. O’Neal formed a committee to study the judiciary in 1912, which led to the 1915 Special Commission on the Judiciary. This Commission was tasked with simplifying the methods of practice and procedure. They proposed several reforms, but the legislature did not act, because they didn’t want to lose control of the courts.

The Beginnings of Judicial Reform

Forty years later, in 1955, the Alabama Legislature established a Commission for Judicial Reform. The Commission’s members were appointed by the Bench and Bar of the State of Alabama to develop rules and procedures to reshape the Alabama judicial system. However, their efforts were largely ignored until the late 1960s when Howell Heflin made judicial reform his primary mission. While serving as the Alabama State Bar President, he called for the First Citizens’ Conference which was held in Birmingham on December 8-10, 1966. Although Heflin was no longer the State Bar President by the time the meeting convened, he served as the leader of the meeting, chaired by Birmingham lawyer Douglas Arant.

Though Heflin claimed it was a success, the First Citizens’ Conference did not result in immediate change. There was support from the State Senate, its efforts led by C.C. “Bo” Torbert (Class of 1954), who later became Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, and Lieutenant Governor Albert Brewer (Class of 1952), but this support was not shared by Governor George Wallace (Class of 1942). The Speaker of the House assigned the bills to the Highway Safety Committee, and those bills never saw the light of day. Still, Alabama Supreme Court Justice Hugh Maddox (Class of 1957) said that it was “the catalyst for the judicial reform that would later occur.”

After the death of Governor Lurleen Wallace, who took office in 1967 following the first gubernatorial term of her husband, George Wallace, Brewer became governor, and the Citizens’ Conference was still in place. The Conference eventually recommended increasing the membership of the Alabama Supreme Court from seven to nine Justices and separated the Court of Civil Appeals and the Court of Criminal Appeals to have three judges each, rather than having one three-judge Court of Appeals.

In 1968, Governor Brewer appointed a Constitutional Revision Commission that was tasked with reviewing and updating the 1901 Constitution. The Constitution had not been substantially revised in the 67 years it had been on the books. Conrad Fowler (Class of 1948) was appointed chairman with William H. McDermott (Class of 1958) serving as vice chairman. Leigh Harrison, former dean of The University of Alabama School of Law (1950-1966), was hired as the executive director, and David Bagwell (Class of 1973) served as Harrison’s research assistant on this project. Over the course of three years, the Commission created an entirely new Constitution. It was during this time that George Wallace was reelected as governor. In 1971, the Commission presented its findings to Governor Wallace, who did not support any reform that could change the balance of power in the state, so the effort to reform the Constitution and the courts was stalled until Howell Heflin was elected as Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court in 1970.

Heflin began the work of judicial reform immediately. In a way, judicial reform was the pet project that he had begun during his tenure as Alabama State Bar President, and now he had reached a point where he could enact real change.

Heflin’s first order of business was to get the judicial system out from under legislative control. Mike Goodrich (Class of 1971), then Heflin’s chief of staff, was tasked with organizing grassroots meetings throughout the state to explain the proposed revisions of the Judicial Article and why those changes were needed.

“When I arrived in the spring of 1971, various bills were introduced that would strengthen the authority of the Supreme Court and allow it to adopt its own Rules of Civil Procedure,” said Goodrich. “A bill was introduced to create a Department of Court Management that [allowed for] a mechanism to alleviate the backlog of cases both at the trial level and at the appellate level.”

In addition to convincing the legislature to grant the state Supreme Court the ability to “promulgate rules of procedure, practice, and pleading for the trial courts,” Heflin also supported the passage of legislation to provide continuing judicial training and education and create the Department of Court Management and the Permanent Study Commission on Alabama Courts. Prior to the creation of the Department of Court Management, the Chief Justice was tasked with managing all aspects of the courts without administrative tools to help with that job. The Department of Court Management also allowed for disciplining judges through methods other than impeachment, which was cumbersome and rarely used. The Permanent Study Commission on Alabama’s Judicial System was directed by Heflin to consider the Judicial Article proposed by Fowler’s Constitutional Commission and became active in the judicial reform effort. By October 1972, the Supreme Court had successfully adjudicated all its cases, and at the beginning of the November 1973 term, the Court of Criminal Appeals had only six pending cases. This was the clearest that the court’s docket had been in recent memory.

“For the first time, you had a streamlined system. [With the] establishment of the Office of Court Management, [the judicial system] wasn’t run like 30-something individual pieces,” said House. “Then, from 1972, the Court had the ability to make the Rules of Criminal and Civil Procedure.... Prior to that, the legislature was the one to make the Rules, and you just couldn’t get anything through.”

The Judicial Article

Though Heflin had small legislative victories early in his tenure as Chief Justice, he knew that court reform would require changing the 1901 Constitution. Under Conrad Fowler, the Constitutional Commission continued its work, despite not being supported by the Wallace administration. While they were tasked with rewriting the entire Constitution, Fowler and his Commission decided to focus just on Article VI, the Judicial Article.

Before the article could pass, it had to get support from the voters. This was a difficult task because the Governor and his followers did not support judicial reform. Even though the Governor was relatively quiet about his position, he still did not want to upset the current balance of power and probably thought that the reforms that Heflin had already achieved were more than satisfactory. Needless to say, Heflin remained unsatisfied.

“In mid-1972, the second phase of judicial reform began,” said Goodrich. “This phase was to incorporate the reforms passed by the legislature into a new constitutional article. This effort would require the vote of the people.”

One of the main perceived issues facing the judicial reform effort was cost. The State brought on consultants who determined that the cost was to be less than 1% of the total budget – far less than was allocated to other branches of government for their operation. Still, organizations like the League of Municipalities and government officials were not supportive.

It was around this time that Heflin convened a Second Citizens’ Conference. Conrad Fowler, a leader at this Citizens’ Conference, explained to its attendees the importance of rewriting the Judicial Article. Heflin also received support from Alabama Supreme Court Justice Hugh Maddox. Maddox was not a natural political ally of the reformers, but he understood that judicial reform was needed, even if the people involved did not agree with him politically. The Conference eventually recommended that the legislature allow the citizens of Alabama to vote on a new Judicial Article — something that the governor hesitated to oppose, as it was arguably the democratic process at work.

On May 22, 1973, the Judicial Article was submitted to the state legislature, introduced by Senator Stewart O’Bannon (Class of 1956) and Representative Bob Hill (Class of 1959). Other Senators who supported the bill included Joe Fine (Class of 1963), Richard Shelby (Class of 1963), and Finis St. John, as well as Lieutenant Governor Jere Beasley (Class of 1962).

Heflin and House mounted a grassroots effort, which began in the northern part of the State, called the “Muscle Shoals Mafia.” House recruited 15,000 people from 50 different organizations across the state, including the Alabama Farm Bureau, the Alabama Motorists Association, the Parent-Teacher Association, the League of Women Voters, the Jaycees, the Alabama Labor Council, the Circuit Judges Association, the District Judges Association, and the Alabama State Bar. They also received support from the mayor of Tuscumbia and president of the Alabama League of Municipalities, William Gardiner, and Circuit Judge Ed Tease (Class of 1964), who helped to lobby the legislature in favor of the new Judicial Article.

“The primary challenge was [securing] adequate funding for the effort,” said House. “Think about it – it was a general election. To give money for this, for court reform, people say, ‘Why should I give you that? I don’t really care.’ I give the Alabama Bar Association a lot of credit; they mounted an extensive campaign to raise the funds.”

Despite all these efforts, the bill still had to make it out of the legislature. It was scheduled as the last bill to come up on the last day of the session, which would terminate at midnight. Representative Hill failed in his first attempt to introduce the bill. Around 8:00 p.m. — with just four hours remaining in the legislative session — he made a final push to reintroduce the bill.

“We brought it up earlier in the evening in the last night of session, and it failed,” said House. “We were devastated. When we brought it up again, there were several amendments proposed on what they call a ‘Judicial Commission’ in various counties. In some counties, you had a Judicial Commission that selected judges, and that was up to each individual county. The people who were proposing these additional amendments were trying to kill the bill.”

House continued, “About 30-45 minutes before [midnight], [Representative Ronnie] Flippo proposed an amendment that took all of those amendments and combined them into one. The people that were against [the bill] thought that Flippo’s amendment would kill it because you had to have the changes that were made in the bill enrolled before it was returned to the Senate for passage – and time was running out.”

But House and Heflin had a trick up their sleeves, which came as a surprise to those who did not support the bill.

“The week before the final day of the legislative session, I had met with the Secretary of the Senate and told him what we were concerned about,” said House. “We wrote up the original House bill like it was but left whole spaces on each page for any potential amendments. When [the bill] came over with Flippo’s amendment, we were able to type it in one of the spaces. At that point, the bill was enrolled and ready to go to the Senate floor for final passage. It passed the Senate with probably about eight minutes to spare, and the opposition in the House was stunned.”

House continued, “It was amazing. It was one of the highlights of my life. At that point, Chief Justice Heflin came to the legislature and thanked and congratulated everybody involved.”

The new Judicial Article was a huge turning point for the Alabama Judicial System. According to John Hayman, author of Heflin’s biography, A Judge in the Senate, eight major changes to the judicial system in Alabama resulted from the Article:

- The State adopted a unified judiciary, with a two-tier trial court system composed of a circuit court and a district court. Municipal courts were retained but were given the option of merging with the district courts.

- The Supreme Court had rulemaking power for civil and criminal rules.

- The legislature became obligated to fund the court system.

- All trial judges had to be lawyers.

- Professional standards were established, with a Judicial Inquiry Commission that had the power to make complaints against judges and a court of the judiciary to hear complaints.

- A commission was established to set judicial salaries that could only be overridden by the legislature.

- The Supreme Court was required to advise the legislature on changes needed in the number of judgeships and jurisdictional procedures.

- Broad administrative power to run the court system was vested in the Chief Justice.

This new Judicial Article took Alabama from having one of the worst judicial systems in the country to being a national model that other states looked at to reform their own systems. But the work was not over.

Implementation Legislation

The Judicial Article provided an outline for the new judicial system, but legislation was still needed to fill in the details. In April 1974, Heflin established an Advisory Commission on Judicial Article Implementation to draft the legislation necessary for the implementation of the Judicial Article. The Commission was led by Joseph F. Johnston and Professor Charles Cole. For two days in June of 1974, the full Commission met. They established five committees: District Court Organization, Personnel and Administration, Fiscal and Budgetary, Municipal Courts and Court-Related Agencies, and Prosecution Services. For many months, the Committees worked on their particular projects until all-Commission meetings were held in October and November of 1974, with the final Commission meeting being held in February 1975. The Commission’s report was delivered to the legislature on March 28, 1975, was 198 pages long, and contained 66 recommendations.

On May 25, 1975, C.C. “Bo” Torbert introduced the bill in the Senate. It was introduced in the House a week later.

Again, Heflin and his team faced timing issues — the bill was presented on the floor during the final day of the legislative session — but they were more prepared this time around. Mike House got 72 of 105 House members to co-sponsor the bill and 25 out of 35 senators. Heflin said, “When they are co-sponsors, they can still change their vote, but it’s a pretty good indication they will vote with you.”

After much debate — mostly over funding — the bill passed the House with a vote of 100-1 and the Senate with a vote of 30-0. Governor Wallace signed the bill on October 10, 1975.

The fight for judicial reform was won through the leadership of Howell Heflin, the strong support and participation of the Alabama Bar Association, a scrappy crew of young lawyers, and the energy of a major grassroots organization.

“The bottom line is it took the combined effort of all parties to make this happen. Heflin, throughout his career, had the ability to pull people together toward a common goal – that was one of his great strengths. I think without his vision and his work ethic, [judicial reform] would’ve never happened. He had the vision, determination, and intelligence to do this, and to pull so many different people together.”

The Modernization of the Rules of Procedure in Alabama Courts

The Judicial Article was not the only aspect of the court system that underwent substantial changes during this time. Mere months before the Judicial Article was passed, after Heflin had convinced the legislature to allow the Supreme Court to make its own Rules, Heflin appointed 15 lawyers to the Supreme Court Advisory Committee on Civil Practice and Procedure to begin the process of writing the Alabama Rules of Civil Procedure.

In 1938, the United States adopted the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, but Alabama’s were not adopted until 1971. Before then, the Alabama legislature, not the Alabama Supreme Court, had rulemaking power for judicial procedure throughout the state. Because Alabama adhered to Common Law, there was no discovery process, and everything was hammered out through pleadings. After the complaint was filed, the opposing party could file a demurer, then a rebutter then the surrebutter and so on and so forth. As Justice Champ Lyons, Jr. (Class of 1965) stressed, the technicalities were dispositive factors of court cases during this time.

“There was an emphasis on pleading and getting the paperwork right,” said Lyons. “We used to say, ‘You have to hold your mouth right.’ As a result, it was difficult for litigants, particularly on the plaintiff’s side, to deal with lawyers who were experts on the technicalities and were able to avoid a case being decided on the merits.”

The new rules, authored by Justice Lyons, were designed to deliver “the just, speedy, and inexpensive determinations of actions” that were decided on the merits of the case rather than the technicalities.

“We had an archaic system that was a disservice to the public, and the time had come to embrace what the federal courts had done in 1938,” said Justice Lyons. “We adapted our practice to a version of the federal rules. It was done by statute in 1971 after Howell Heflin became Chief Justice he was able to get the legislature to confer rulemaking power on the Supreme Court. There was support on both sides of the Bar by then. There were some obstinate old-timers that didn’t want to do it, but of course Justice Heflin was a force of nature and had a very persuasive personality.”

Chief Justice Heflin established the Supreme Court Advisory Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure, which consisted of fifteen members: Oakley W. Melton, Jr. (Class of 1951), who chaired the committee, Timothy M. Conway, Jr. (Class of 1949), Frank Donaldson (Class of 1954), J. Foy Guin, Jr. (Class of 1947), Judge James O. Haley, Francis H. Hare, Sr., Judge Joseph M. Hocklander (Class of 1950), Jerome A. Hoffman (Alabama Law professor), James L. Klinefelter (Class of 1951), Jack Livingston (Class of 1950), Justice Champ Lyons, Jr. (Class of 1965), Mayer W. Perloff, Ira D. Pruitt, Sam W. Pipes IV (Class of 1966), and Thomas E. Skinner.

“The awareness that the court was going to do this made it important for the people in the Bar to get on board and have their input,” said Lyons. “The thing that I remember that was really positive about our committee is that we had lawyers from both sides of the Bar who would check that at the door and come in and try to do something as if they were in a judicial capacity that was fair and balanced.”

The Rules, after being promulgated on January 3, 1973, went into effect six months later in July. Justice Lyons eventually wrote four editions of the Rules that govern civil procedure in Alabama still today, and Justice Hugh Maddox published the Alabama Rules of Criminal Procedure in 1990.

“Reflecting on the legacy of these Alabama Law alumni, I feel very proud of the impact our institution has had on the state. Part of our mission is to educate and inspire leaders who make a difference in our State, the nation, and the world, and this shows that our alumni have been doing just that for many years.”

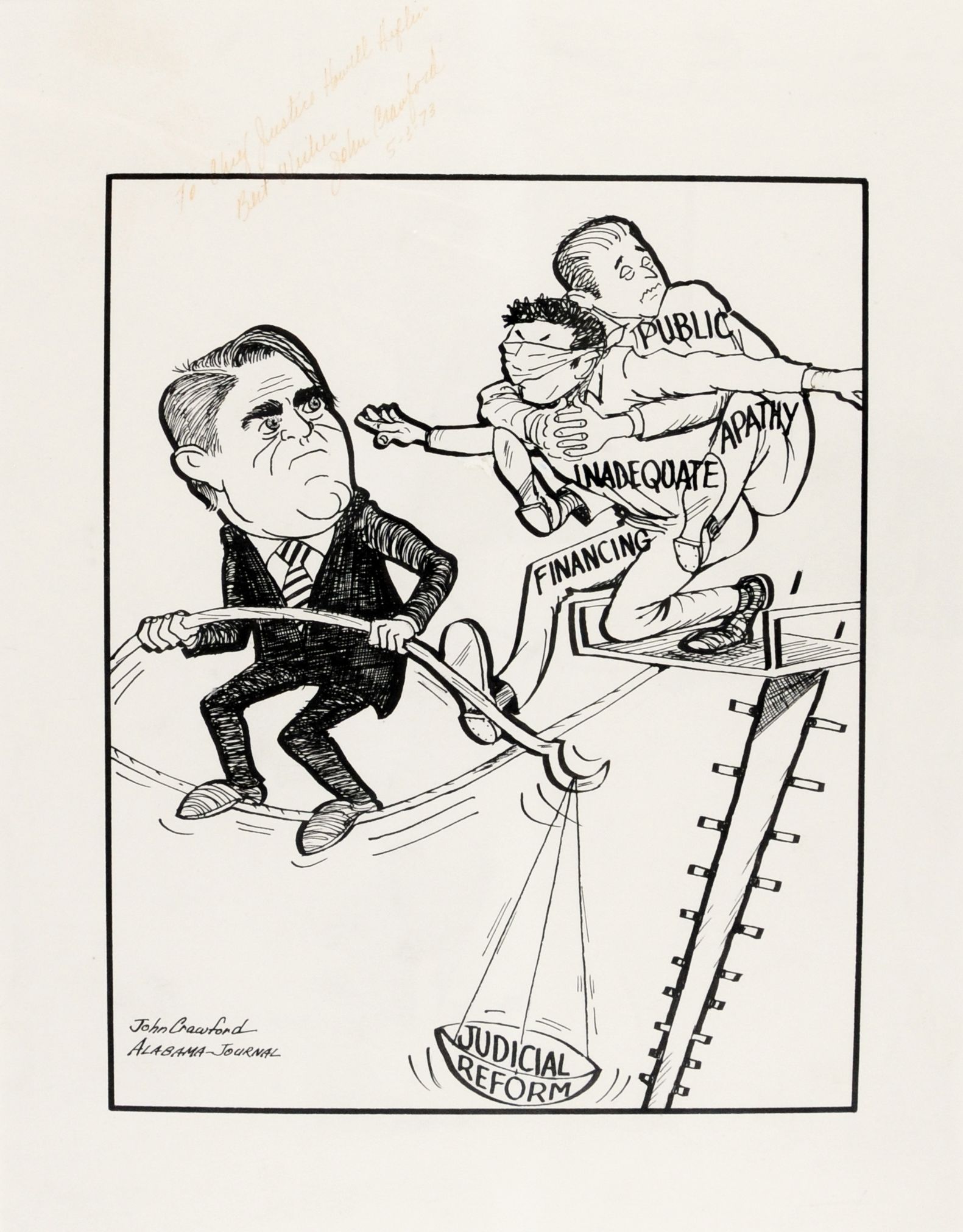

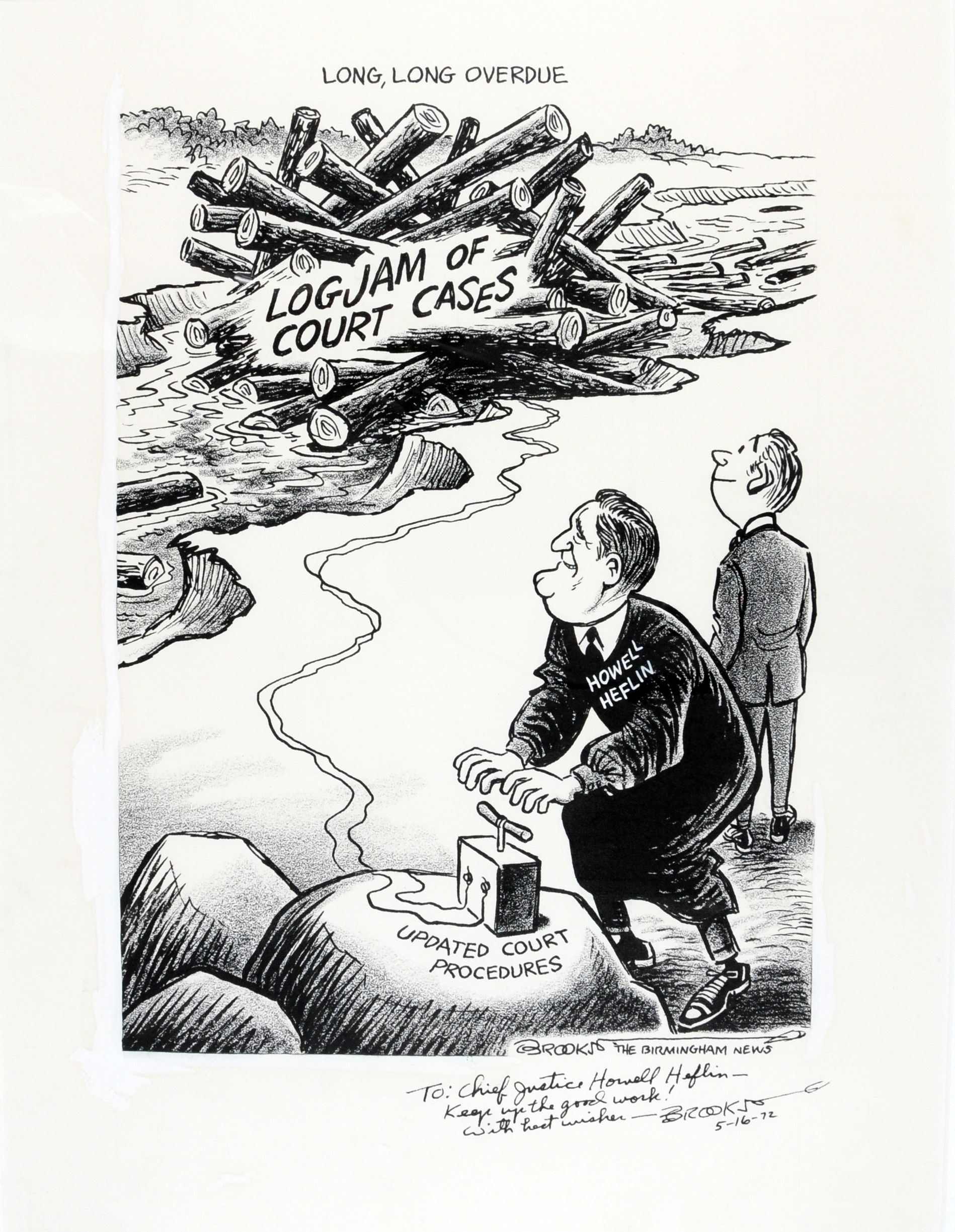

Courtesy of the John C. Payne Special Collections of the Bounds Law Library as part of the Howell Thomas Heflin Collection.

Courtesy of the John C. Payne Special Collections of the Bounds Law Library as part of the Howell Thomas Heflin Collection.

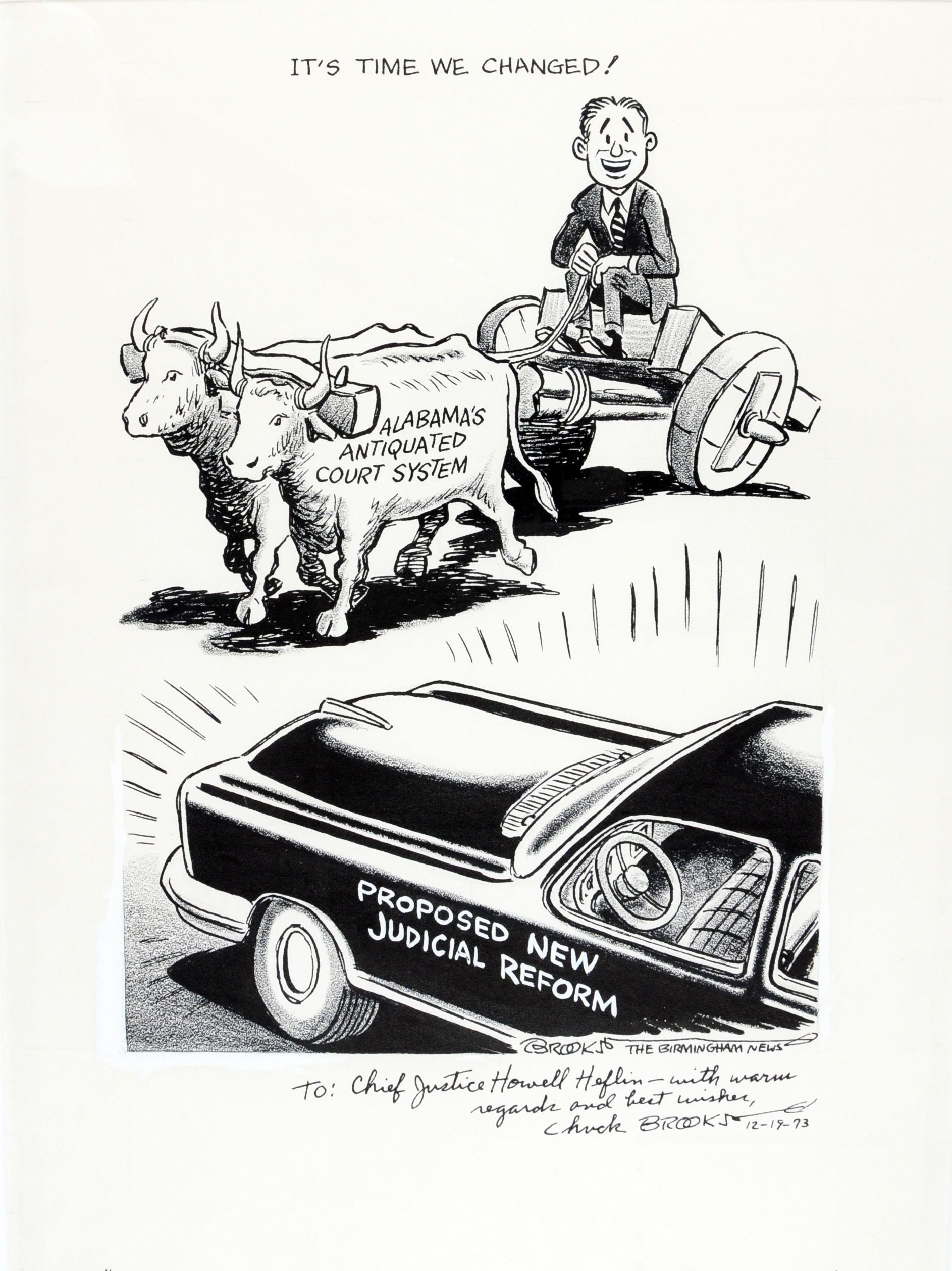

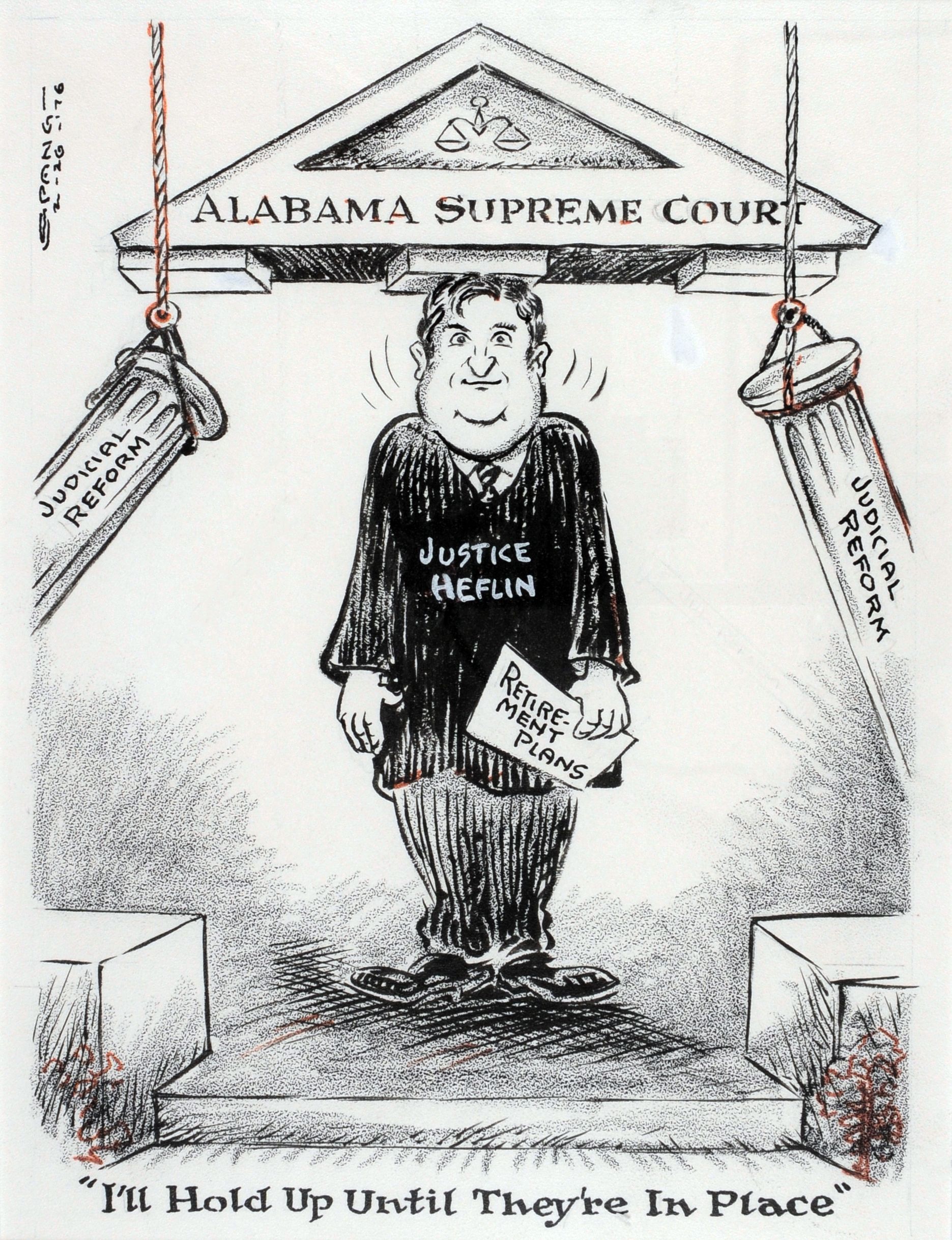

Courtesy of the John C. Payne Special Collections of the Bounds Law Library as part of the Howell Thomas Heflin Collection.

Courtesy of the John C. Payne Special Collections of the Bounds Law Library as part of the Howell Thomas Heflin Collection.

Heflin casting his vote for the Judicial Article. Photo courtesy of the Bounds Law Library at The University of Alabama School of Law.

Heflin casting his vote for the Judicial Article. Photo courtesy of the Bounds Law Library at The University of Alabama School of Law.

Committee members at the first inaugural meeting of the Rules Committee. Photo courtesy of Justice Champ Lyons Jr.

Committee members at the first inaugural meeting of the Rules Committee. Photo courtesy of Justice Champ Lyons Jr.

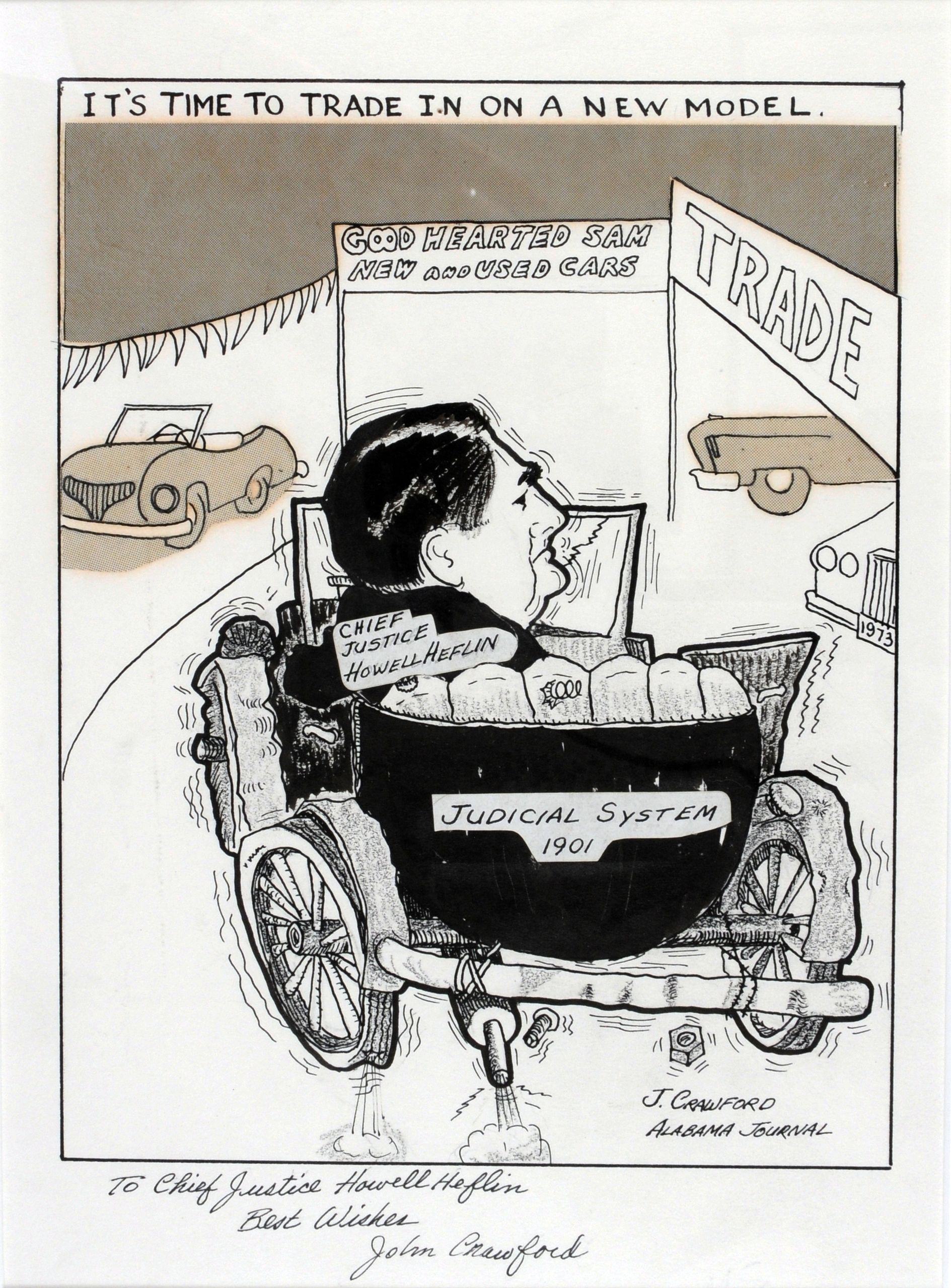

Courtesy of the John C. Payne Special Collections of the Bounds Law Library as part of the Howell Thomas Heflin Collection.

Courtesy of the John C. Payne Special Collections of the Bounds Law Library as part of the Howell Thomas Heflin Collection.

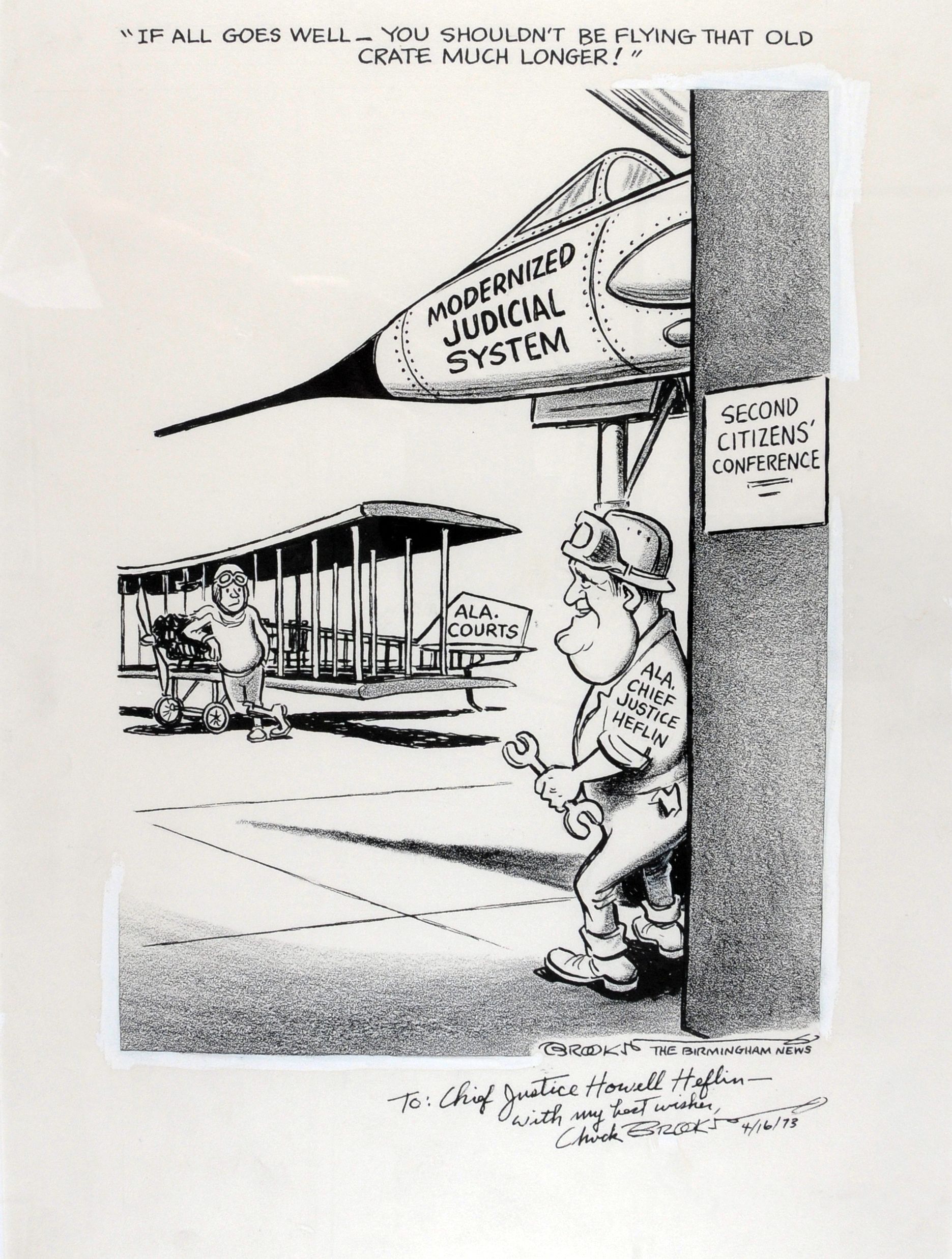

Courtesy of the John C. Payne Special Collections of the Bounds Law Library as part of the Howell Thomas Heflin Collection.

Courtesy of the John C. Payne Special Collections of the Bounds Law Library as part of the Howell Thomas Heflin Collection.

Chief Justice Howell Heflin works at his desk at the Supreme Court of Alabama. Photo courtesy of the Alabama Supreme Court and State Law Library.

Chief Justice Howell Heflin works at his desk at the Supreme Court of Alabama. Photo courtesy of the Alabama Supreme Court and State Law Library.

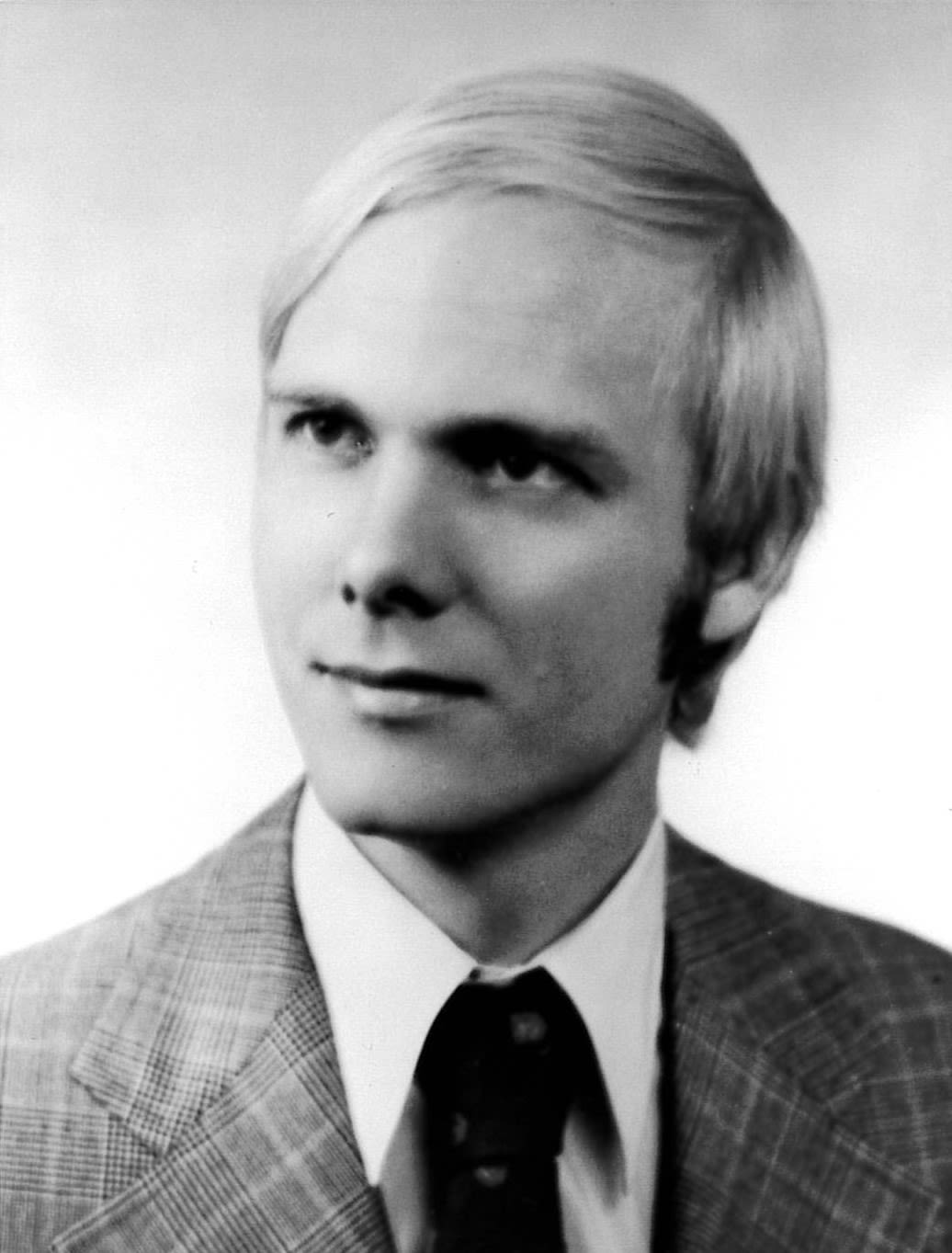

Mike House served as Heflin's chief of staff as Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court then later as U.S. Senator. Photo courtesy of the Alabama Supreme Court and State Law Library.

Mike House served as Heflin's chief of staff as Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court then later as U.S. Senator. Photo courtesy of the Alabama Supreme Court and State Law Library.

Courtesy of the John C. Payne Special Collections of the Bounds Law Library as part of the Howell Thomas Heflin Collection.

Courtesy of the John C. Payne Special Collections of the Bounds Law Library as part of the Howell Thomas Heflin Collection.

Courtesy of the John C. Payne Special Collections of the Bounds Law Library as part of the Howell Thomas Heflin Collection.

Courtesy of the John C. Payne Special Collections of the Bounds Law Library as part of the Howell Thomas Heflin Collection.

The Justices of the Alabama Supreme Court and members of the Supreme Court Advisory Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure after the Rules of Civil Procedure were adopted in January 1973. The Rules went into effect later that year in July. Photo courtesy of Justice Champ Lyons Jr.

The Justices of the Alabama Supreme Court and members of the Supreme Court Advisory Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure after the Rules of Civil Procedure were adopted in January 1973. The Rules went into effect later that year in July. Photo courtesy of Justice Champ Lyons Jr.

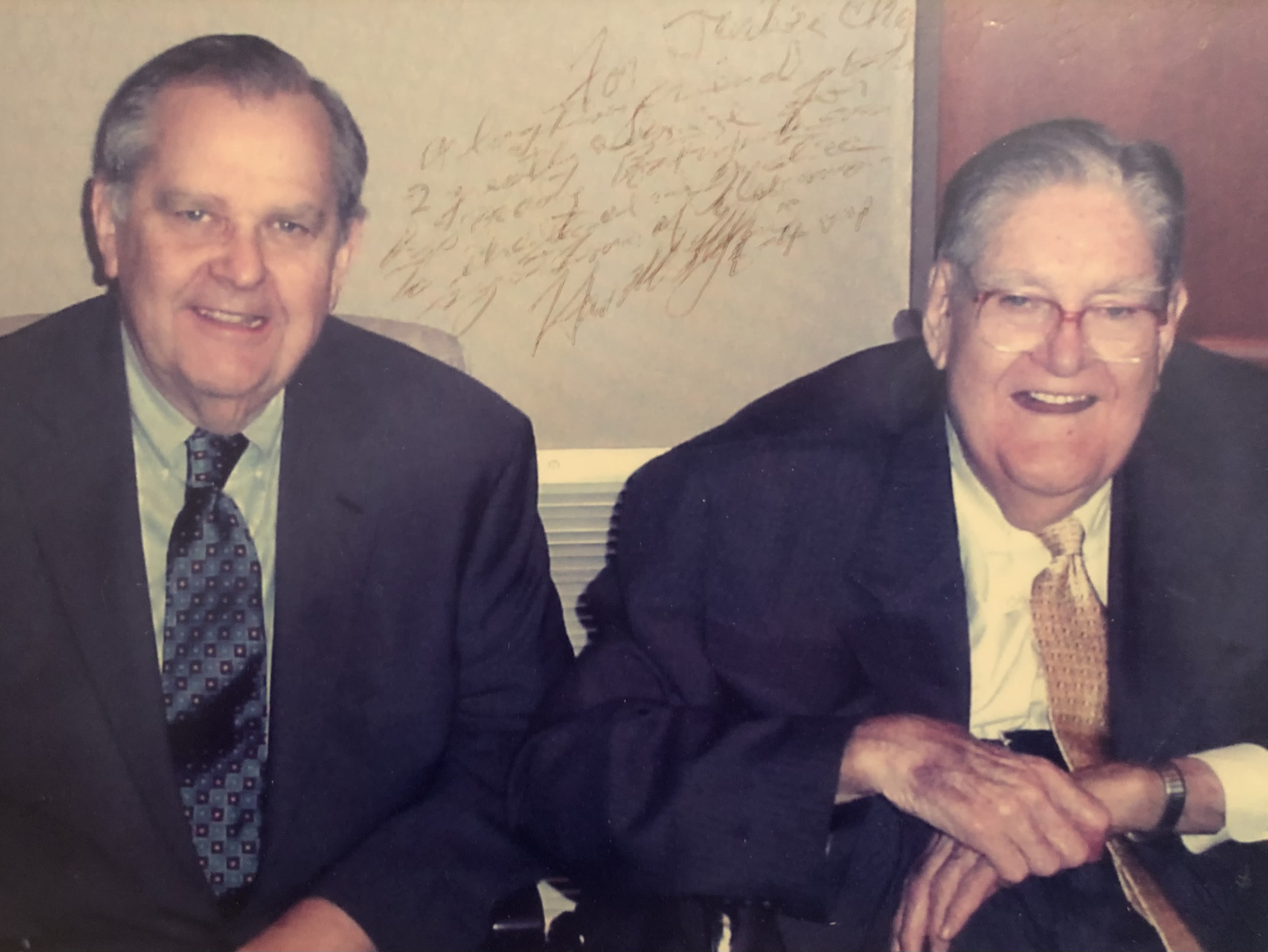

Justice Champ Lyons Jr. and Chief Justice Howell Heflin. Photo courtesy of Justice Champ Lyons Jr.

Justice Champ Lyons Jr. and Chief Justice Howell Heflin. Photo courtesy of Justice Champ Lyons Jr.