The Modernization of Tuscaloosa's Built Environment

The Architecture of Don Buel Schuyler

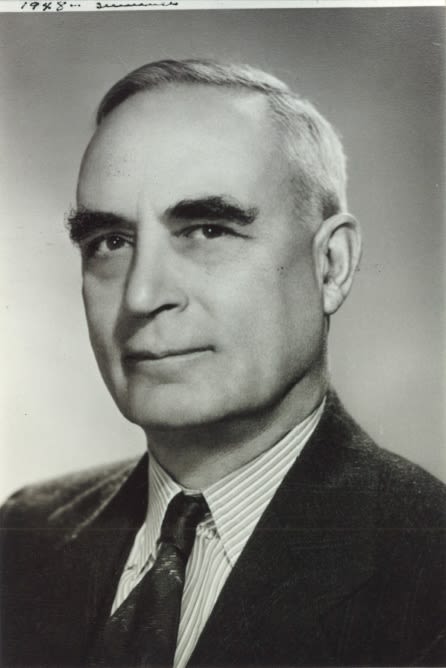

Who is Don Buel Schuyler

There was no escaping destiny for Don Buel Schuyler. Coming from a family of carpenters and constructions workers, a career in architecture just made sense. Schuyler’s career spanned six decades (1910s - 1960s) and three cities: Wichita, Mobile, and Tuscaloosa.

Many people are familiar with Schuyler, having learned about efforts to nominate some of his outstanding architecture to the National Register of Historic Places, such as the Queen City Pool and Bath House (1943) and Stafford Methodist Church in Stafford, Kansas (1926). However, knowledge of Schuyler and

his architecture is limited and fragmented. People in Wichita know about his Wichita career; people in Tuscaloosa know about his Tuscaloosa career; and people in Mobile have never heard of him. It is time that people know all about Schuyler’s great works regardless of geography.

Schuyler was an architect, landscape architect, engineer, inventor, innovator, developer, and ultimately city planner. This exhibit, the first for Schuyler, reveals his architecture in its entirety. Additionally, it reveals the magnitude of Schuyler’s contributions to the built environment of Tuscaloosa.

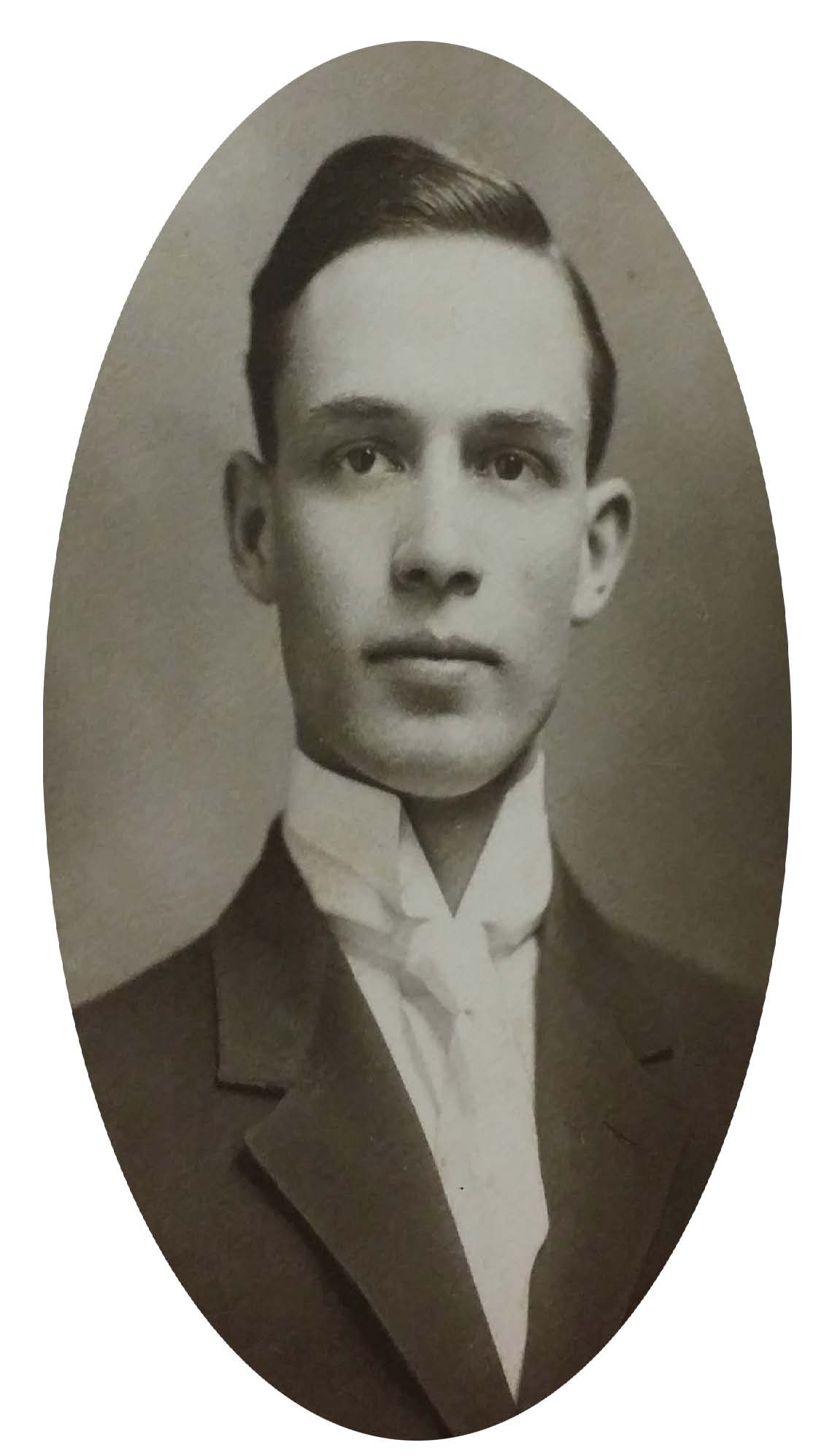

Don born in 1888, was the second child born of Buel M. and Florence C. Schuler.

Don grew up in Englewood Kansas. In 1903, Buel, a carpenter by trade joined his brother, Frank, in the construction business in Wichita, Kansas.

Schuler Brothers Construction quickly became a family tradition and in 1904 at the age of 16, Don joined the family business.

In 1907 he chose to follow his brother, Ivan, who went to study art at the local college in Wichita, Fairmount College (now Wichita State University).

Don graduated in 1911 with “honors in chemistry and Cum Laude with a major in physics-mathematics.”

Drawing sewer lines at the Engineer Office was not to his liking, so Schuyler entered the University of Illinois in 1913 to study Architecture. This decision prepared Schuyler for a lifetime of opportunities. Schuyler was a fitting recipient for induction in the engineering honor society, Tau Beta Pi.

Throughout the rest of his long career, Schuyler epitomized Tau Beta Pi’s motto of: “Integrity and Excellence in Engineering.” Frank Lloyd Wright hired Schuyler straight out of college and in the winter of 1916, Schuyler traveled to Wright’s residence and design studio, Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin. He did not spend much time at Taliesin before heading back to Wichita to serve as site architect for the construction of the residence of future Kansas governor, Henry J. Allen.

While working as a draftsman in the Kansas City, Missouri Engineer Office, Schuyler applied for a concrete beam and slab patent. This engineering patent is one of the most telling exhibit images, as it reveals Schuyler’s understanding of building design and foreshadows future architecture.

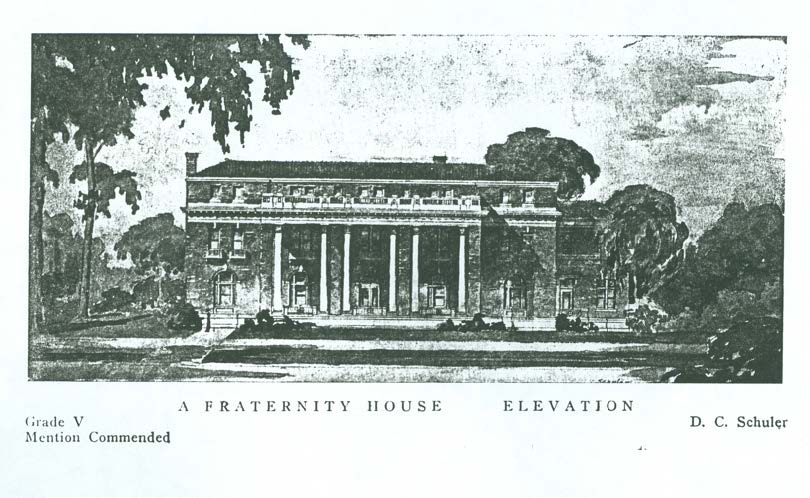

The Architectural Yearbook, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (1916)

Schuyler (incorrectly referenced as “D. C.” Schuler) received praise for his senior class project, which was published in the School of Architecture’s annual. While the fraternity house drawings showcase Schuyler’s understanding of Classical scale, proportion, rhythm, and stylistic embellishment, the ode to Classical Revival architecture does not represent a sign of things to come (Courtesy of the University of Illinois Archives).

Although Schuyler parted ways with his mentor, his Wichita architecture reflected the influence of their historic association. He is perhaps best known during this period for three churches he based on the design of Wright’s Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois (1906). These include the Riverside Church of Christ (1922), First Methodist Church of Augusta, Kansas (1925), and the Stafford United Methodist Church of Stafford, Kansas (1926). The June 1922 issue of American Garage & Auto Dealer praised the building Schuyler designed for the Schollenberger brother’s automobile business as “having been devised and planned by an efficiency expert…”

By the 1920s, Schuyler had achieved success. The local press, the Wichita Beacon and Daily Eagle, regularly praised his architecture. He had transformed a bare Prairie landscape into a hybrid tropical and old fashioned garden. His home and garden were the highlight of the neighborhood. Lured by distant prospects, Schuyler left his success behind in 1926.

Wichita, KS.

M. C. (Cliff) and Gwendolyn H. Naftzger House, 312 North Belmont (1917)

In 1917, Schuyler designed one of Wichita’s best examples of Dutch Colonial Revival architecture in the

Naftzger House. The home is crowned by a handsome gambrel roof punctuated by three pedimented

dormers and features a one-story portico with a balustraded deck, entablature, dentils, and fluted columns

and pilasters (Courtesy of Gene A. Ford).

The Henry J. Allen House, 255 N. Roosevelt (1917)

The Henry J. Allen House is the source for those who want to understand Schuyler’s modern architecture. The house includes a floating roof, clerestories, stained glass, streamlined design, and the organic relationship between architecture and site. The Henry J. Allen House was also at the center of a revival of interest in Schuyler’s architecture in the early 1990s (2016 Courtesy of the Henry J. Allen House Archives).

Schollenberger Brothers Building (Wichita Automobile Company) (1920)

Schuyler designed this commercial building for Morris, George, and Harvey Schollenberger, who sold bicycles and automobiles. Completed in 1920, the modern, three-story building featured a showroom fronted by wrap around plate glass windows on the first floor, a garage on the first and second floors, and parts storage and offices on the third floor (Courtesy of Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum).

Victory Arch (Dedicated May 19, 1919)

In 1919, Schuyler was commissioned to construct a soldiers’ memorial arch commemorating victorious

troops returning from Europe at the end of World War I. Built at a cost of $4,000 to $5,000 dollars, the Victory Arch featured wood construction and a white stucco finish. It stood 40 feet high and spanned 70 feet. Never intended to be a permanent installation, the World War I memorial was demolished in 1920 (Courtesy of the Schuler Family Archives).

Hugh Gill House, 302 N. Bluff (1922)

With its low-pitched hip roofs, projecting porch and porte cochere, stained glass windows, and ground hugging horizontal lines, the Gill House is a modest version of the Henry J. Allen House. (2016 Google).

Riverside Church of Christ drawing The Wichita Eagle (April 29, 1923)

Dedicated in April 1923, the Riverside Church of Christ was the first of three churches designed by Schuyler that were based on the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois (1906).

Mobile, Al.

Though Wichita was in the middle of an architecture boom, Schuyler sought out the next adventure. Construction in Florida was booming and in 1926 Schuyler decided to pack up his family and head south. However, the family had only made it as far as Mobile, AL when they heard the Florida boom busted.

The Schuyler’s decided to remain in Mobile, but that meant starting from the beginning for Schuyler and his business. An attractive home in the Wimbledon neighborhood of Springhill helped the family socialize with those who had the financial means to hire an architect.

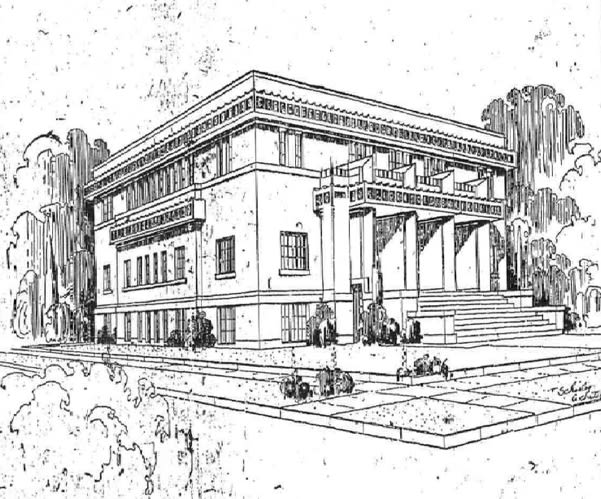

The Mobile Public Library (1928)

The Mobile Public Library, now the Ben May Main Library, with its temple-like façade featuring a long run of bold columns, symmetry, and an entablature, opened in 1928. Schuyler executed the drawings for

lead architect George B. Rogers (Courtesy of Gene A. Ford).

Thomas Byrne Memorial Library, Spring Hill College, Mobile, Alabama (2016)

Mobile architectural historian John Sledge wrote: “The Thomas Byrne Memorial Library is a sophisticated edifice with one of the most distinguished architectural pedigrees in the city.” The Library, completed in 1931, is an interpretation of Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia Statehouse (1789). In turn, Jefferson based his design on the Maison Carree (circa 2 AD) in Nimes France. (Courtesy of the Springhill College Archives) (2016 Courtesy of Gene A. Ford).

The Modernization of Tuscaloosa

In 1936 Schuyler moved his family to Tuscaloosa to educate his daughters at The University of Alabama. The lingering effects of the Great Depression and a suspension on construction during World War II forced Schuyler to find creative solutions to money and material shortages. He found that answer in an inexpensive and readily available material: concrete. Designed in myriad forms and styles, his concrete buildings include the Clements-Barnes House (1939-1941), the County Activities Building (1940), Queen City Pool (1943), his residence, Possum Hollow (1940-1945), 1 Wood Manor (1947), and the Christian Science Church (1953).

In the late 1940s, Tuscaloosa faced a shortage of classroom space. Schuyler solved the problem building 18 schools, including: Holt High School (dedicated in 1944), Samantha School (1946-1947), and Alabama Elementary School (1953). When he thought the downtown district was becoming overcrowded, he worked with City Hall to create favorable zoning for commercial and residential developments. Schuyler built the Jitney Jungle supermarket (1948), the Cloverdale Garden Apartments (1948), and Stafford Elementary School (1955). His work also extended to churches. The Christian Science Church (1953) and Wesley Methodist Church (1954) feature Schuyler’s signature modern style with references to Frank Lloyd Wright.

By the late 1950s, Schuyler’s productivity was slowing down but not his creativity. In a bold move, he abandoned concrete in favor of steel, glass, and bricks for the composition of the First Federal Savings and Loan Bank (1960.) The outcome was fresh, sleek, polished, and modern.

A Legacy Remembered

Schuyler retired in 1964 at the age of 76. As Tuscaloosa’s premier architect Schuyler did more than design buildings; he built institutions and infrastructure. His residences, schools, churches, commercial buildings, recreational facilities, and industries transformed Tuscaloosa into a modern city. For the eight

remaining years of his life, he must have had some satisfaction seeing his contributions to the modernization of Tuscaloosa’s built environment.